Knee injuries are extremely common, especially because the knee joint itself has so many different components and bears the stress of our body throughout a lifetime.

The knee joint is composed of 4 main structures: ligaments, cartilage, bones, and tendons. This article will attempt to discuss the most common knee injuries related to these 4 structures of the knee, and discuss what you can do about them.

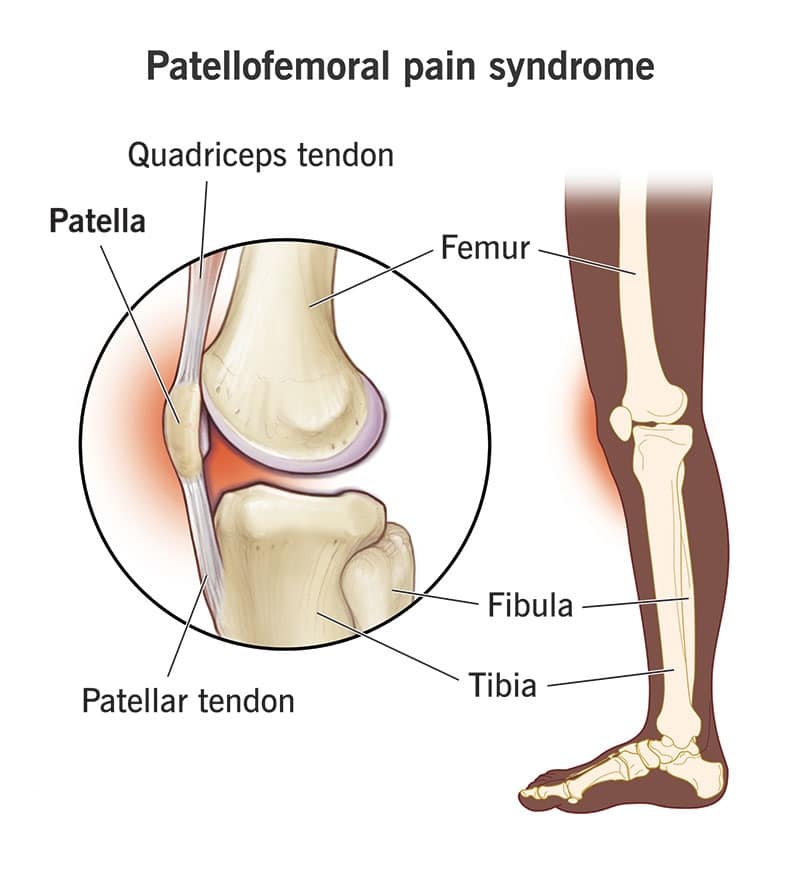

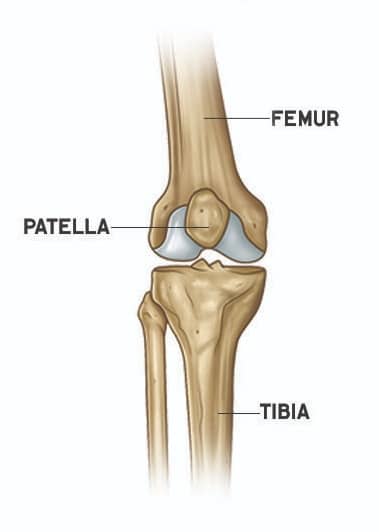

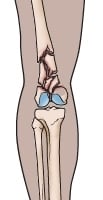

First, let’s go over some basic anatomy of the knee. There are 3 bones that make up your knee: the thigh bone or femur, the shinbone or tibia, and the kneecap or patella.

Cartilage covers all the contact points of one bone touching another. It’s present on the back of the kneecap and the ends of the shinbone and thighbone. Cartilage helps your knee glide smoothly when you bend and straighten it, to prevent experiencing clicking, grinding and pain.

Ligaments connect bones to other bones to give our skeleton structure and stability. There are 4 major ligaments in the knee we’ll be covering in this article, but more of that to come soon! Ligaments help keep our skeleton together and giving it structure. Tendons are bundles of fibers that connect our muscles to bones. Tendons do have more give to them than ligaments, allowing you to contract and relax your muscles.

So now that you’ve been given a brief overview of the 4 main structures of the knee, let’s take a closer look at the first structure, ligaments.

Ligament Injuries of the Knee

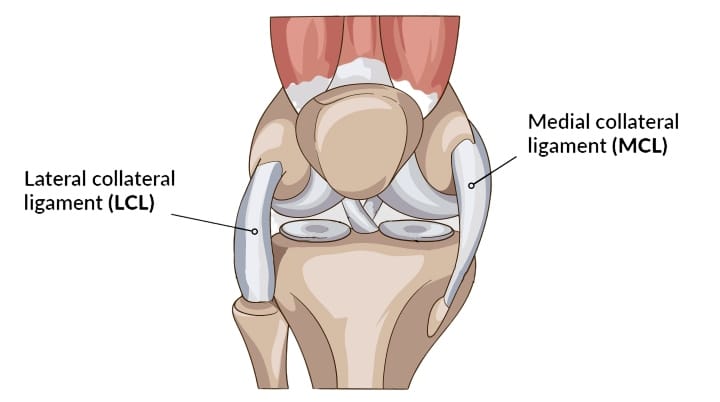

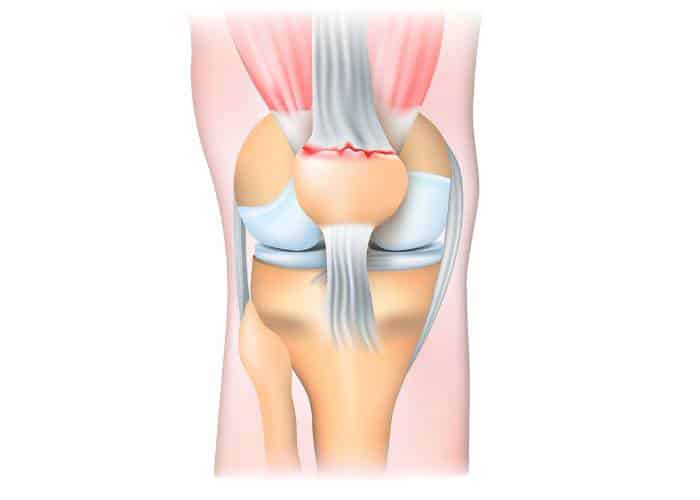

There are four major ligaments in your knee that give it structure and stability: two cruciate ligaments and two collateral ligaments in each of your knees.

Cruciate ligaments are located deep inside your knee joint. There are two cruciate ligaments in the knee, which form an “x” pattern. This pattern is important to preventing too much movement of our femur on our tibia bones relative to one another. After all, we don’t want our bones to slide too far! The cruciate ligaments mostly provide stability while also preventing too much forward or backward sliding of the bones relative to one another. However, the cruciate ligaments also play a role in preventing excessive knee rotation (what little rotation it naturally has).

Collateral ligaments are located outside of your knee joint. There are two collateral ligaments in the knee, one on the inside and the other on the outside of each knee. The inside collateral ligament is called, medial collateral ligament or more commonly referred to simply as “MCL”. The outer collateral ligament is called, lateral collateral ligament or more commonly referred to simply as “LCL”. The collateral ligaments work together to give stability while also preventing too much side to side movement of your femur and tibia bones.

As you can see, your knee is stabilized on all four sides with the cruciate ligaments taking the front and back, while the collateral ligaments stabilize the inside and outside. This provides your knee tons of stability, holding your knee together like a “brace”. Of course, our ligaments can only take so much force in any given direction, causing overstretching, tearing and sometimes even full rupture (detachment) of the ligament! Let’s cover the most common ligament injuries of the knee next.

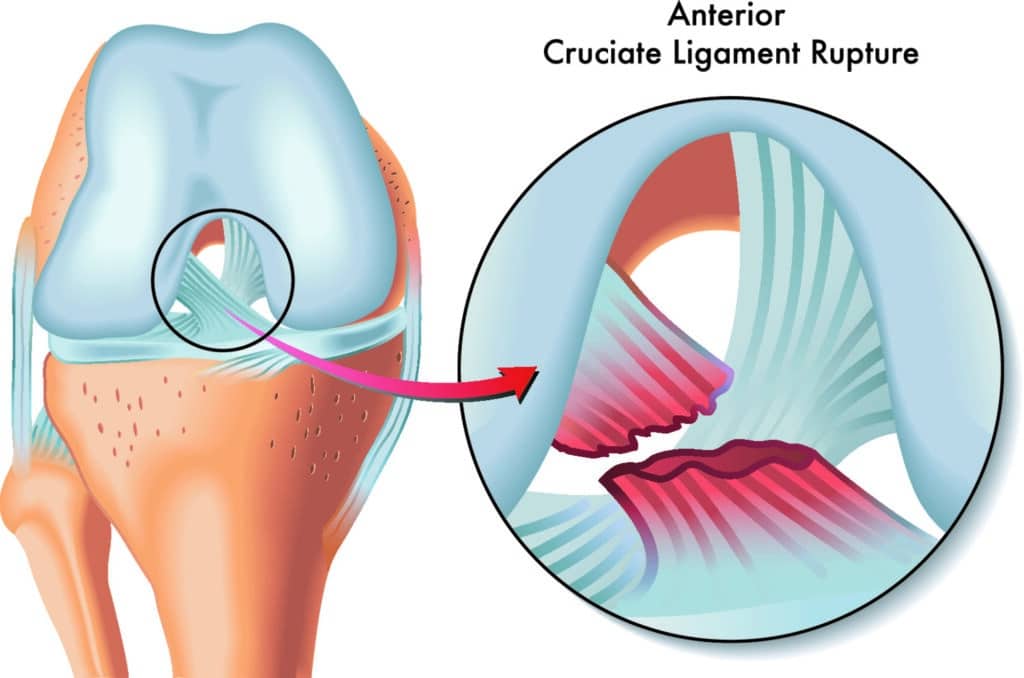

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries

You’ve probably heard of athletes injuring their ACL. That’s because it’s one of the most common sports injuries, especially when there’s a lot of pivoting or quick direction changes involved, like in football or soccer (the other football.)

There are a few different ways you can injure your ACL. For example:

- Quickly cutting in different directions

- Abruptly stopping or slowing down from a run

- Colliding or direct contact

- Landing wrong after a jump

About 50% of all ACL injuries involve damage to another part of the knee as well.

Sprain Severity by Grade

Ligament injuries are called sprains and are graded on a scale from 1 to 3.

- Grade 1

- Grade 1 sprains involve mild damage. The ligament has stretched slightly, but still provides stability to the knee joint.

- Grade 2

- Grade 2 sprains are when the ligament is so stretched that it’s become loose. These sprains are commonly referred to as a partial tear. It’s pretty rare to partially tear an ACL, as they usually tear completely or close to it.

- Grade 3

- Grade 3 sprains are commonly called complete tears. They’re the most severe type of sprain, and involve a ligament that’s pulled off of the bone or torn in half, leaving the knee extremely unstable.

Most people with ACL injuries notice their knee making a distinct popping noise, or even feeling weak to the point of nearly giving out. Some other common symptoms can include:

- Swelling and pain, especially within the first 24 hours of the injury

- Decreased range of motion

- Tenderness to the touch

- Difficulty walking (along with discomfort)

Diagnosing

The best way to diagnose an ACL tear is with a physical exam. Your doctor will take a brief medical history, ask about your symptoms, and then move your knee around. They’ll take range of motion measurements and use various other tests to make a diagnosis.

Although it’s usually not necessary, your doctor may order some imaging to get a better look at your injury. X-rays don’t show ligament tears, but help determine whether there’s a broken bone involved. MRI scans, on the other hand, create images of soft tissue, so they’ll show if there’s damage to your cartilage or meniscus.

Treatment

When it comes to ACL tears, it’s imperative to get your knee stable again so it doesn’t keep giving out or sliding too far forward. Not only is this super painful, but it can cause damage to your cartilage and menisci if left alone. Eventually, it can lead lead to arthritis and even more problems as well.

Your treatment options depend on a few things like your age, activity level, and other health conditions. Most older adults can get back to their normal lifestyle through rehabilitation.

At physical therapy, your goal is to strengthen the muscles surrounding your knee, especially the hamstring muscles in the back of the thigh. The physical therapist will work with you to manage your pain and swelling, and to fully restore your knee’s range of motion. They will also teach you how to make simple modifications that allow you to safely return to your daily activities.

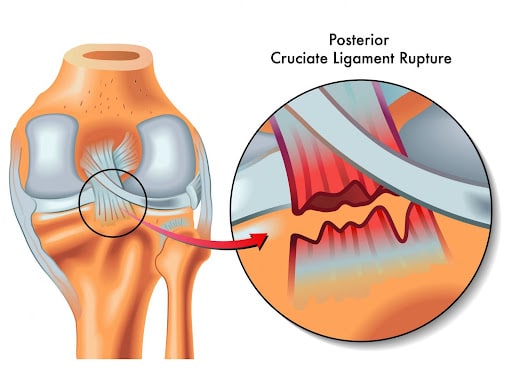

Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) Injuries

The PCL is made up of two bundles, about the size of your pinky finger, and are responsible for keeping your shinbone from sliding too far backwards.

Something as simple as a misstep rarely causes PCL injuries. Generally, there needs to be a pretty powerful force involved, like taking a blow to the front of your knee while it’s bent, either during sports or a car accident. Even the force from twisting or hyperextending your knee can cause damage to your PCL.

The posterior cruciate ligament is the least likely ligament to get injured. In fact, PCL injuries are so subtle that they can be difficult to even evaluate. Similar to the ACL, PCL injuries usually involve damage to some other part of the knee as well. But unlike the ACL, most PCL injuries tend to be grade 2 partial tears and often heal on their own.

Some common symptoms of PCL injuries include:

- An increase in pain immediately after the injury

- Swelling that causes stiffness and even a limp

- Difficult walking

- Feeling like your knee is unstable, to the point of giving out

Diagnosing

Your doctor will review your symptoms and do some testing to check the structural integrity of your injured knee. They may notice it sagging backwards when you bend it, especially when it’s bent more than 90°.

Other tests, like x-rays and MRI’s, may help confirm their diagnosis. Unfortunately, if the injury is older than 3 months, your imaging may appear normal. While the PCL injury won’t show up on the x-rays themselves, they can show if a piece of bone tore off when the ligament tore.

Treatment

Luckily, most PCL injuries don’t require surgery in order to heal. Some doctors may suggest a special type of brace that helps keep the tibia from sliding backwards, as well as crutches to keep weight off of your knee.

Once your swelling has gone down, you’ll want to start a PT program so you can get back to your normal activities. The main goal of physical therapy will be to strengthen the leg muscles that support your knee, restore your function and improve your motion. Your recovery will depend on the severity of your injury and whether you damaged other parts of your knee.

Collateral Ligament Injuries

Collateral ligament injuries are often contact injuries, meaning they’re typically the result of a direct blow that pushes your knee sideways. Injuries to the LCL (lateral collateral ligament) are caused by a hit to the inside of the knee, pushing it outwards, whereas injuries to the MCL (medial collateral ligament) are from a hit to the outside of the knee, pushing in inwards.

Overall, most injuries happen to the MCL compared to the LCL. If you do manage to injure your LCL, more than likely you also damaged another part of your knee since the outside of the knee is fairly complex.

Pain on either side of your knee is a common symptom of collateral ligament injuries. You’ll notice the pain (and swelling too) on the outside of your knee if it’s your LCL and on the inside of your knee if it’s your MCL. Both injuries can leave you feeling like your knee is about to give out.

Diagnosing

Similar to other tendon injuries, an exam is the best way to diagnose collateral ligament injuries. Doctors will check range of motion and use different kinds of tests, as well as compare your injured knee to the healthy one. They may also order imaging to further confirm details.

While x-rays won’t show your ligaments, they will indicate whether a piece of bone was torn off when you got injured. MRI’s, on the other hand, will show an overall image of the collateral ligaments and other soft tissue.

Treatment

There are several ways you can treat collateral ligament injuries. Ice is typically the first line of defense. You’ll want to apply it for at least 15-20 minutes every hour.

It’s also important to protect your knee from the same force that originally caused the injury in the first place. Depending on your lifestyle, you may have to switch up your normal daily activities for a while so you can avoid any potential risky movements. Your doctor may take it a step further by recommending you use a brace and possibly even crutches. This will help protect the injured ligament from further stress by keeping your weight off of your leg.

One of the most effective ways to treat a collateral ligament injury is with physical therapy. The therapist will create a plan of care that focuses on restoring function and strengthening the muscles surrounding your knee. As your knee becomes more stable and your gait is steady, you’ll work on other functional goals, like returning to the gym or doing light yard work. Eventually you’ll progress to more complex movements and motions.

Surgery isn’t usually necessary for most collateral ligament injuries. However, if the tear won’t heal properly or another ligament is involved, your doctor may want to go in to repair it.

Meniscal Tears

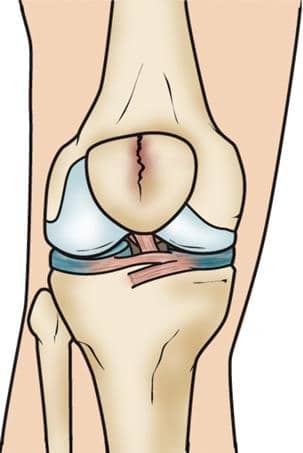

The meniscus is a C shaped piece of cartilage that sits between your shinbone and thighbone. Each knee has two menisci which act as shock absorbers and provide stability for the entire knee. They’re also responsible for transferring weight from one bone to another.

Meniscus tears are one of the most popular types of knee injuries. They’re typically sports-related, but tears can happen from something as simple as pivoting. Even awkwardly twisting in your chair as you stand up can be just enough to tear your meniscus.

Tears in the meniscus are defined by their look and their location. Common meniscus tears include radial, flap, and handle tears. Some tears are a result of degenerative changes that happen gradually over time. This is because as you age, your tissue becomes worn, making it more prone to tearing.

If you tear your meniscus, you may feel a popping sensation. Most people are still able to walk or even continue playing in their game after it happens. Only after the next few days will you notice gradual swelling and stiffness. Some other symptoms include:

- Pain and tenderness

- Locking or catching

- Feeling of your knee giving out

- Decreased range of motion

Diagnosing

You’ll want to see your doctor right away if you suspect that you have a meniscal tear. During the exam, they will perform the McMurray test, which involves bending, straightening, and then rotating your knee. These movements put tension on your meniscus and will cause pain or a clicking noise if it’s torn.

A lot of knee injuries have similar symptoms to a meniscus tear, so your doctor will more than likely order imaging to confirm the diagnosis. X-rays won’t show your meniscus, but can be used to rule out other causes of pain from dense bony structures, like osteoarthritis. On the other hand, MRI’s create an image of your soft tissue, including ligaments, tendons, cartilage, and of course, your meniscus. MRI’s are considered the preferred method for diagnosis due to its high accuracy rates.

Treatment

There are a few different factors that will determine which treatment is best for you, like age, prior activity level, and symptoms. The size, type, and location of your tear also comes into consideration. There’s a rich blood supply, called the red zone, that’s located on the outer ⅓ of your meniscus. Tears in this area, like longitudinal tears for example, often heal on their own.

Tears located outside of the red zone are considered in the white zone. Since this area lacks a significant blood supply, it doesn’t receive nutrients from your blood, which means it’s not able to heal itself. And because these tears don’t respond well to conservative treatment, they’re typically trimmed through surgery.

Luckily, if your swelling has gone down and your symptoms have started to go away, your doctor may recommend a less invasive form of treatment.

One of the most effective ways to recover from a meniscus tear, with or without surgical intervention, is with physical therapy. The physical therapist creates an exercise program designed specifically to improve strength and restore mobility to your knee. In the beginning, the main focus is on your range of motion and as you progress, they’ll add in strengthening exercises. You’ll also receive an exercise program that you can do at home on the days you don’t have physical therapy. That way, you can keep making progress, even on your days off.

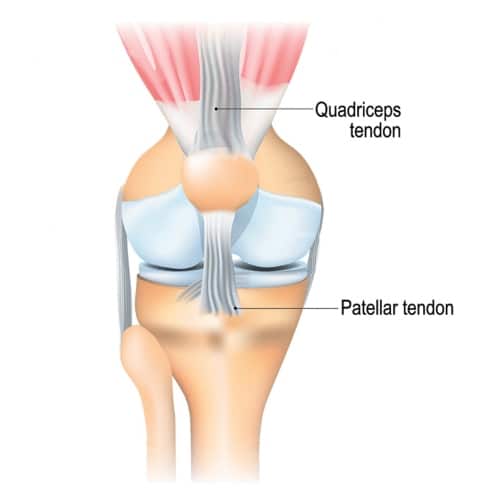

Tendon Injuries

Now, let’s take a look at tendon injuries. Tendons are cords of strong fibrous tissue that keep your muscles attached to your bones. Your knee has two main tendons: the patellar tendon and the quadriceps tendon.

The patellar tendon attaches your patella (kneecap) to your tibia (shinbone). Its main responsibility is holding the bones together and providing stability. The quadriceps tendon attaches the quadriceps muscles to the patella. Both tendons work together, along with the muscles in the front of your thigh, to straighten your knee.

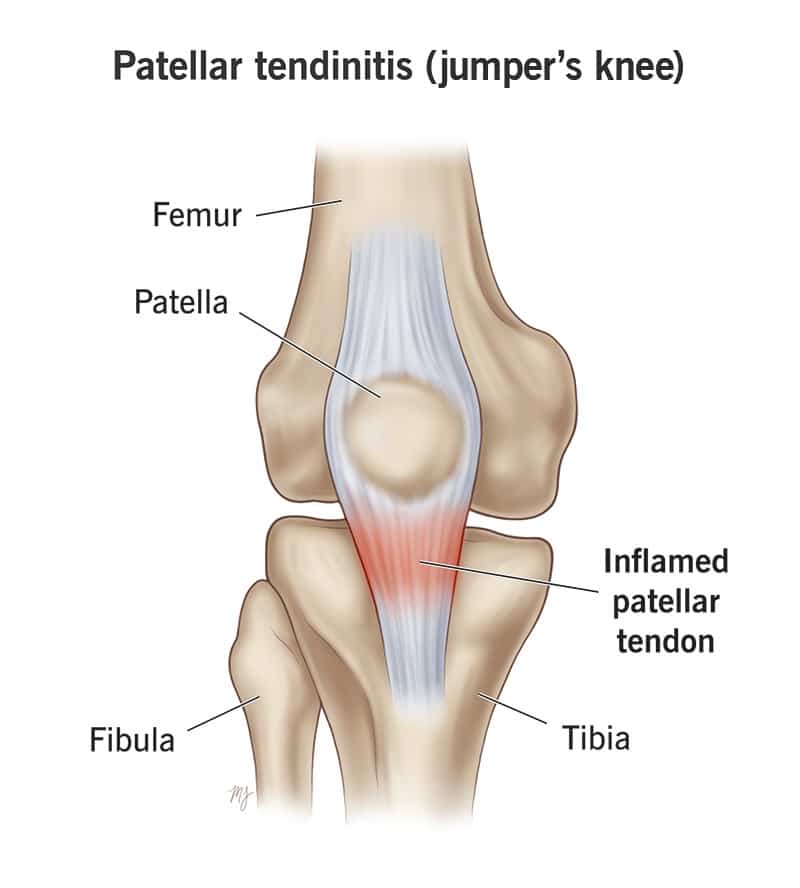

Tendinitis

One of the most common tendon injuries is tendinitis. Tendinitis is inflammation (or swelling) of a tendon. It’s typically an overuse injury resulting from repeated movements, like sprinting or jumping, that strain and stress your tendons. After a while, tiny tears start to add up and make the tendon weak and sore. The pain usually worsens over time and can even become debilitating if left untreated.

Tendinitis can develop in both the patellar tendon and the quadriceps tendon.

As the name suggests, patellar tendinitis refers to pain just below your kneecap caused by inflammation of the patellar tendon. It’s often called “jumper’s knee” since repetitive jumping is one of the leading causes of patellar tendinitis. Quadricep tendinitis refers to pain in the front of your knee, just above your kneecap, caused by inflammation of the quadricep tendon.

While the majority of tendinitis injuries are from overuse, things like obesity, poor flexibility, and alignment issues are contributing factors as well. Some other risk factors include:

- Age

- Since tendinitis progresses over time, older adults over the age of 40 are naturally at a higher risk.

- Physical Activity

- Activities that involve lots of sprinting, jumping, or abrupt direction changes can increase your chances of developing tendinitis.

The most common symptom of tendinitis is pain that gets worse as your knee moves. You may also experience swelling, tenderness, stiffness, and a burning sensation as well.

Treatment

When it comes to treating tendinitis, physical therapy is one of the most promising options. If you’re in the early stages of tendinitis, the goal is to reduce inflammation quickly and decrease pain. For long-standing tendinitis, on the other hand, the focus is on improving your function and range of motion.

Through exercises and other therapeutic techniques, the physical therapist will work on strengthening your injured knee and correct any muscle imbalances that you may have.

As you progress through your plan of care, your therapist will add new exercises to your routine that are both challenging and rewarding. They want to ensure that your body is able to handle your normal activities before you start them back up again. And while all injuries are unique, many people with tendinitis recover in around 4 to 6 weeks with physical therapy.

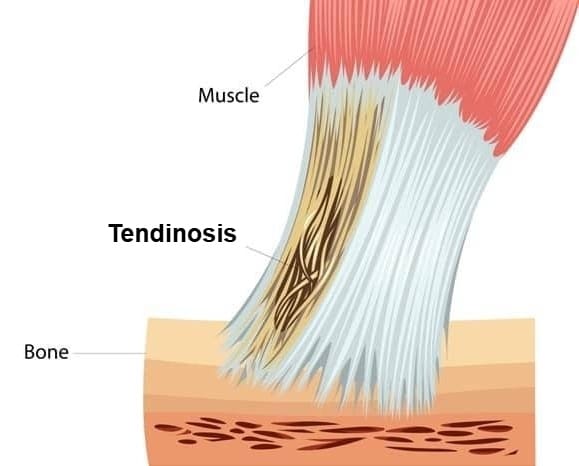

Tendinosis

Tendinosis is the result of chronic degeneration of a tendon over time.

As you know, tendons attach muscles to bones. They’re primarily made up of a bunch of collagen fibers bundled together. If you have tendinosis, these bundles start to unravel and break down. Scar tissue begins to build up in between the tiny gaps, and as a result, the fibers become firm, scarred, and thick.

With patellar tendinosis, you may feel a burning, painful sensation, especially when you move or touch your knee, as well as weakness, like your knee is going to give out. Unlike tendinitis, tendinosis doesn’t cause redness, swelling, or inflammation. In fact, there may not even be any noticeable pain in the early stages either. Some people only notice an unsteady feeling when the tendon is strained. It’s in the later stages when scar tissue is involved that the tendon usually becomes more sensitive.

Causes

Likely the most common cause of tendinosis is from repetitive strain. By nature, tendons are pretty resistant to tearing, but aren’t necessarily stretchy. Because of this, they can become injured very easily and heal quite slowly. So, when you overuse your tendon by repeating the same activities and movements too often or too vigorously, tiny tears start to appear. If you continue for long enough, that’s when tendinosis develops.

This is especially true if you’re an athlete or have a job that involves doing the same movements day after day. In these situations, you’re more prone to experiencing repetitive strain injuries in general. And when they do happen, the want (or need) to get back to work sometimes makes it impossible to stop long enough for the tendon to heal properly.

Some other factors that may cause tendinosis include age, prior injuries, and chronic inflammation. As you get older, your tendons naturally weaken, which increases your risk of degeneration. Similarly, old injuries and even previous surgeries can leave your tendon weak if it never fully healed.

Now, if you already have tendinitis, it may lead to tendinosis down the road. The chronic inflammation that comes with tendinitis can cause damage to the patellar tendon, weakening it and as a result, trigger the degeneration process.

Treatment

Treating tendinosis is extremely important. If left untreated, your tendon will continue to deteriorate until it fails.

One of the most painful ways the tendon can fail is by suddenly rupturing or tearing. It may also give out completely, meaning it can no longer hold your weight. When this happens, a different body part is forced to carry the load, which causes even more problems.

Depending on how advanced your tendinosis is, it could take up to 6 months to heal and return to your normal physical activities. The biggest goal for any tendinosis treatment is to get your tendon to start building new collagen again.

Icing is considered the standard for treating most musculoskeletal pain, and tendinosis is no different. Ice causes vasoconstriction, which is just a fancy way of saying it constricts blood flow. This is beneficial if you have tendinosis because it discourages new blood vessels from forming in the tendon and in turn prevents tissue remodeling from occurring (which is that scar tissue buildup mentioned earlier.)

While it’s critical to avoid strenuous activity and allow your tendon to heal, it’s equally important to prevent muscle loss from inactivity as well. A great way to find this middle ground is with physical therapy.

At physical therapy, you will learn exercises that safely strengthens and stabilizes your knee while still allowing your tendon to heal. Some of the exercises will be part of an exercise program you can do at home on the days you don’t have therapy. Your therapist will also help modify certain activities so you can slowly start adding them back into your daily life.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS) (Runner’s Knee)

The next type of tendon injury is called patellofemoral pain syndrome (or PFPS). PFPS involves pain in your patella and the surrounding area, specifically where the patella connects to the femur.

It’s often referred to as “runner’s knee” because it’s a common injury among runners, but really anyone can get it. One of the biggest causes is from overuse. Most people develop runner’s knee after repeated stress from vigorous physical activities, like squatting, climbing stairs, or jogging. It can also be the result of suddenly changing up your normal workouts, whether it’s an increase in frequency, duration, or intensity.

Another cause of runner’s knee is abnormal patellar tracking. Basically, when you bend and straighten your knee, the kneecap moves back and forth inside a groove on top of your femur, called the trochlear groove. If the patella is off track, it can cause pressure and irritate your knee.

While things like alignment problems with your ankles or hips can cause tracking issues, most of the time it’s simply due to muscle weakness. When you flex and extend your knee, the quadriceps muscles and tendon keep your kneecap in place, while your hip muscles control the femur. If these muscles are weak, they aren’t able to do their job keeping your kneecap moving along that groove.

Treatment

The best course of treatment for runner’s knee is to first and foremost stop running and doing any other strenuous physical activity until you’re able to do them without any pain. Like most knee injuries, you’ll want to focus on improving your strength and mobility, and of course, reduce pain as well. Luckily, you can accomplish all of these things with physical therapy.

At PT, your therapist will teach you a series of exercises that focuses on strengthening and stabilizing your knee. You can even do them safely in your home too. As you progress, more advanced exercises will be added to your regimen. The therapist will work to improve your range of motion and gradually increase your activities until you’re able to return to running without pain.

Patellar Tendon Tear

Now let’s take a look at tendon tears. The patellar tendon attaches to the front of your thigh muscles and is responsible for straightening your leg. Tiny tears in the tendon can make it quite difficult to walk and do other daily activities, whereas large tears can be debilitating.

There are two types of tendon tears, either partial or complete.

- Partial tears are smaller and typically don’t disrupt the tendons ability to function. Think of the tendon as a rope. It may be stretched with a few stray fibers, but it’s still technically in one piece.

- Complete tears are just as the name suggests, where the tendon is completely torn and separated from your kneecap. Unfortunately, you can’t straighten your knee without this attachment in place.

Typically, the patellar tendon tears close to where it attaches to the kneecap, and can even break off a piece of bone with it. If a tear is the result of a medical condition though, like from tendinitis, the tear usually occurs more in the middle of the tendon rather than the end.

Causes

There are a few different ways to tear your patellar tendon. First, is through an injury. The patellar tendon is quite stable. It takes a strong force to cause tearing, like a blow to the front of your knee from a fall or some other form of direct contact.

Another common cause is from jumping. The tendon can tear when your foot is planted on the ground and your knee is in a bent position, like you’re about to jump or you’re coming down from a jump. In fact, this is so common among runners and jumpers that it’s actually often referred to as “jumper’s knee.”

Most people notice a tearing or popping sensation when they tear their patellar tendon. It’s typically followed by pain and swelling, and sometimes you can’t straighten your knee either. Some other symptoms may include bruising, tenderness, cramping, and difficulty walking, to name a few.

Diagnosing

To diagnose a patellar tendon tear, your doctor will test how well you can straighten (or extend) your knee. This can be slightly painful, but it’s important to help identify whether or not there’s a tear.

Your doctor may also order some imaging to help confirm their diagnosis. When the patellar tendon tears, the kneecap moves out of place and is usually quite obvious in x-rays. MRI’s come into play when you need a more complete image. They show soft tissue, so you’ll be able to see how much of your tendon is torn and where exactly the tear is located.

Treatment

Your treatment will all depend on the size of your tear. Most smaller, partial tears respond well with rehabilitation, but complete tears almost always require surgery in order to recover.

Preventing further damage is key, so you may have to wear a brace to keep your knee straight. You can expect to stay in the brace for about 4-6 weeks. Your doctor may also recommend crutches too so you don’t put any weight on your injured leg.

Like most knee injuries, physical therapy is an excellent way to treat patellar tendon tears. Once the pain and swelling goes down, you can begin working on your range of motion and strength. If you’re wearing a knee brace or immobilizer, your exercises may look a little different. You may start off with straight leg raises to strengthen your quadricep muscles, and as time goes on, you’ll be able to gradually unlock your brace and move a bit more freely. The therapist will add more strengthening exercises as you continue to heal.

Quadriceps Tendon Tear

Your quadriceps tendon attaches the 4 quadricep muscles to the top of your kneecap. It works with your quad muscles and the patellar tendon as a sort of pulley system to straighten your knee from a bent position.

Like patellar tendon tears, tears to the quadricep tendon can be either partial or complete. Partial tears don’t disrupt the tendons ability to fully function. The same rope analogy from before applies here too. Complete tears involve the tendon separating entirely from the bone or being split into two separate pieces. When this type of tear occurs, your quad muscles aren’t anchored to the kneecap and therefore the pulley system no longer works, making it impossible to straighten your knee.

Causes

Generally, tears happen when there’s a heavy load on your knee while it’s partially bent and your foot is planted on the ground. Picture awkwardly landing after jumping to catch a football. That force on your knee is just too much for your tendon to handle and it tears as a result. Falls, lacerations (deep cuts), and direct blows to the front of your knee can also cause quadriceps tendon tears.

Not to mention, you’re more likely to tear your quadriceps tendon if it’s weakened. This can be from things like tendinitis, or chronic diseases such as gout or rheumatoid arthritis. Sitting and staying off of your feet for long periods of time to the point where your tendons and muscles lose flexibility and strength, can be an issue as well.

Most people feel a ripping or popping sensation when they tear their tendon. This is usually followed by pain and swelling near the kneecap. Some also notice bruising, cramping, difficulty straightening their knee, or their kneecap beginning to sag where the tendon is torn.

Diagnosing

Diagnosing a quadriceps tendon tear is quite similar to diagnosing a patellar tendon tear. The doctor will do some testing, which may be uncomfortable or slightly painful, to see if there is in fact a tear.

Imaging, like side-view x-rays, can help confirm the diagnosis as well. MRI’s aren’t usually necessary since a physical exam is sufficient. However, they can identify the location of the tear, as well as if the tear is partial or complete. MRI’s also rule out other knee injuries that have similar symptoms.

Treatment

There are several different things to consider when it comes to treating a quadriceps tendon tear. For instance, your age, activity level, and the type of tear all factor into this decision. Most tiny, partial tears can heal without surgical treatment.

Once the pain and inflammation has gone down, you’re ready to start physical therapy. Your main goal is to regain strength and range of motion in your knee. The therapist will create an exercise program that focuses on this goal, and they will add more exercises to your program as time goes on.

Eventually, you will be able to get back to your favorite physical activities. You may have to make some modifications in the beginning to protect your knee, but as you heal and feel more confident, you can remove the precautions.

If you need surgery to repair your tear, your rehab may look a little bit different (depending on the type of tear and how complex the surgery is.) Most repairs heal in about 4 to 6 months, but can take longer if you have other medical conditions or if you were pretty inactive before your injury. Many people need a good 12 months or so before they reach all of their goals and can safely return to playing sports at full speed.

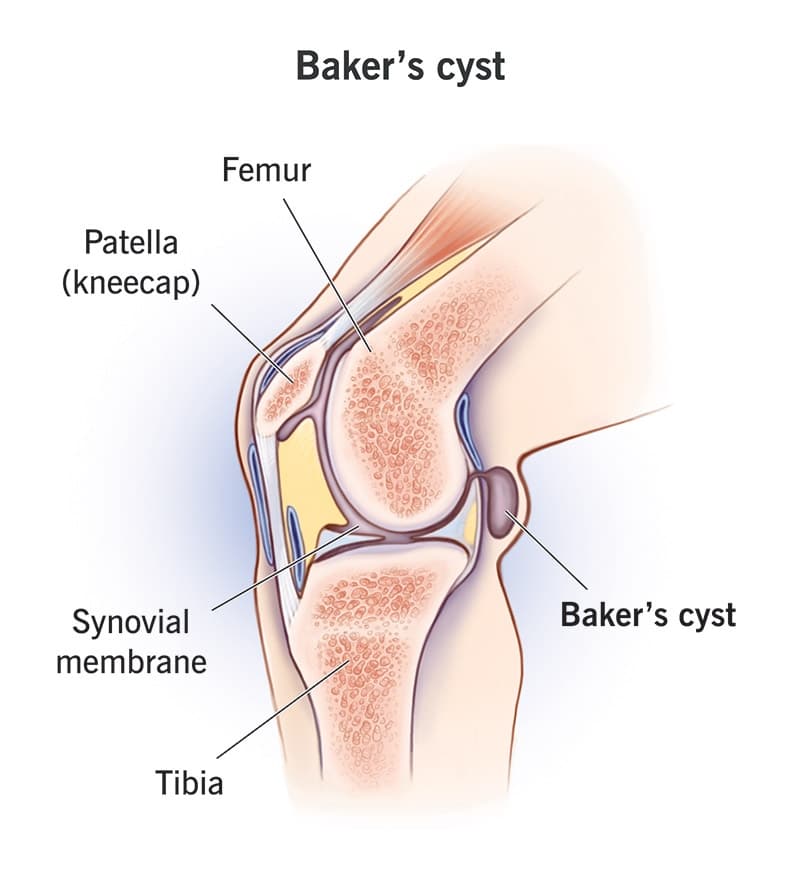

Baker’s Cysts

A Baker’s cyst is a growth that forms on the back of your knee caused by excess fluid. Basically, when your knee is swollen and inflamed, fluid can only drain in one direction: backwards. The sac behind your knee fills up with that fluid and as a result, becomes a Baker cyst.

The bump is the most obvious symptom of a Baker’s cyst, and is often accompanied by pain, stiffness, and difficulty bending the knee. Although, some people develop a Baker cyst and don’t even realize because they don’t experience any symptoms.

Any type of damage that involves swelling in your knee joint can trigger a Baker’s cyst. Arthritis and gout are among the leading causes, since they’re conditions characterized by inflammation. Other causes include sprains, dislocations, overuse injuries and meniscus tears. Ligament damage, like ACL, MCL, LCL, and PCL tears often elicits Baker cysts as well.

While anyone can develop a Baker’s cyst, there are some groups of people that have a higher likelihood. People who put a lot of stress on their knees for work or a hobby, athletes, and middle aged to older adults all run a greater risk of Baker cysts.

Be Cautious

For those with a Baker’s cyst, it’s important to be cautious and keep a close eye on it. One of the biggest complications people face is the cyst rupturing or breaking. This can happen if the sac fills up too quickly or if there’s too much pressure, causing it to burst. Picture a water balloon on the back of your knee that eventually pops when it’s overfilled.

There are a whole slew of other symptoms that can occur if your cyst ruptures. You may experience a stabbing, sharp pain in your knee, swelling in your lower leg and calf, nerve damage, and a condition called compartment syndrome, where you feel extra painful pressure in your muscles.

Diagnosing

The first thing you should do is go see your doctor. They’ll take a look at the bump and ask about your symptoms. There may be visible discoloration in the lower part of your leg, similar to having a blood clot. They might order imaging, like x-rays or an MRI, to rule out anything serious. Luckily, Baker’s cysts are benign, meaning they aren’t cancerous.

Treatment

Treating a Baker’s cyst is pretty straightforward. Typically, once the damage that caused the cyst has healed, the fluid goes away. If your cyst is on the larger side, your doctor may drain it so you can move easier.

You’ll want to avoid whatever physical activity that prompted your injury in the first place so you don’t make your condition any worse. It’s also a good idea to apply ice several times a day for at least 15-20 minutes at a time. Some use a compression sleeve or bandage around their knee to reduce swelling, as well as elevating their leg.

Probably the best option for treating a Baker’s cyst is with physical therapy. A good physical therapist will focus on the reason the cyst developed, as well as any secondary issues caused by the cyst.

At PT, you’ll work to strengthen your muscles and stabilize your knee joint. The therapist will teach you exercises that improve your ability to control your knee and increase flexibility. They will also give you a home exercise program so you can continue progressing even on the days you don’t have therapy. As your range of motion gets better, the physical therapist will add new exercises that will challenge (and heal) your knee.

Fractures Of The Knee

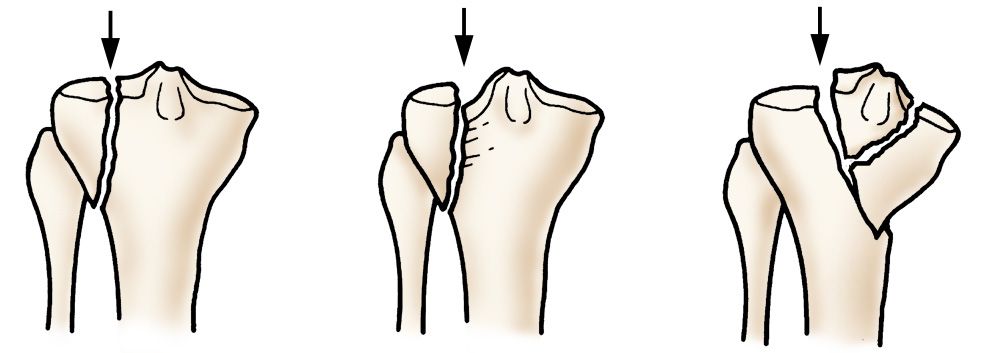

A fracture is classified as a break, either partial or complete, of a bone. When it comes to the knee, breaks can occur in the patella, femur, and tibia.

Patellar (Kneecap) Fractures

The patella, or kneecap, is the small bone that sits in front of your knee joint, where the tibia (shinbone) and femur (thighbone) meet. It connects the front of your thigh muscles to the tibia. It also protects your knee as a whole. The underside of the patella, as well as the ends of the femur, are covered in articular cartilage. This cartilage helps your bones glide as you move your knee.

The patella is the most common of the 3 knee bones to break. The break may be a simple two-piece break or it may break into several tiny pieces. Fractures can happen at the top, bottom or center of the patella, and sometimes even in multiple areas at once.

Let’s take a closer look at the different kinds of patellar fractures.

Types Of Patellar Fractures

- Stable Fracture

- Stable fractures are nondisplaced, meaning the bone pieces stay where they are and are only separated by a millimeter or 2. Typically, the bones don’t shift or move while they heal.

- Displaced Fracture

- Unlike a stable fracture, displaced fractures involve separated pieces of bone. The smooth surface of the joint is also disrupted as well. Since the pieces of bone don’t line up correctly anymore, most displaced fractures need surgery to put everything back together.

- Comminuted Fracture

- This type of fracture occurs when the bone shatters into multiple pieces. They can be either stable or unstable, depending on the pattern of the fracture.

- Open Fracture

- An open fracture is when your broken bone sticks out through your skin. This kind of fracture usually takes a longer time to heal because it damages surrounding soft tissue.

Your patella essentially acts as a shield for your entire knee joint, which makes it vulnerable to fractures. Some common causes of patellar fractures include:

- Falling directly on your knee

- Direct impact blows to the patella

- Collision between your kneecap and dashboard during a car accident

If you fracture your patella, it may be extremely difficult, or even impossible, to straighten your knee, stand, or walk. There’s almost always pain and swelling, and sometimes bruising too.

Diagnosing

Doctors will examine your knee in order to diagnose a patellar fracture. They can often feel the edges of the fracture, especially if it’s a displaced fracture.

They’ll also check for hemarthrosis, which is basically blood leaking from the fractured end of the bone and collecting in the open space of the joint. It’s often quite obvious when this is happening, as it causes pretty painful swelling in your knee. Your doctor may drain the blood to relieve some of the pressure and pain.

Your doctor may also order x-rays as well. Getting x-rays from several different angles helps find the fracture and gives a good view of how the pieces of bone are aligned.

Treatment

Whether or not you need surgery, physical therapy plays a huge role in getting you back to doing the things you love. Since you typically have to keep your knee immobilized after a patellar fracture, your knee can become stiff and weak. Physical therapy will focus on decreasing that stiffness, improving your range of motion, and then strengthening your thigh muscles.

As you progress, you’ll be able to bear weight again on your leg. You will start with exercises that involve simply touching your toes to the ground, then work your way up to putting weight through your entire leg.

Complications

Patellar fractures can be tricky, which is why there can be some complications even after the most successful treatment. For instance, you can develop posttraumatic arthritis. Essentially, the cartilage covering your bones becomes damaged, causing inflammation and pain as a result.

Some people experience permanent muscle weakness after a patellar fracture, specifically in their front thigh muscle. While it’s usually not debilitating, you could permanently lose range of motion in your knee.

One of the most common complications with fracturing your patella is chronic pain. Many experience long-term aching in the front of the knee, and is usually accompanied by stiffness and muscle weakness. Without proper exercising and strengthening movements, your knee is more likely to lock up and cause some permanent damage. This is why it’s so important to start rehabilitation quickly, before your complications get worse.

Distal Femur (Thighbone) Fractures

Your femur, also known as the thigh bone, is the bone connected to the top of your knee. Most femur fractures occur at the distal end, which is the part right above the knee joint that looks like an upside-down funnel.

Types Of Distal Femur Fractures

- Transverse Fracture

- A transverse fracture is when the bone breaks straight across.

- Comminuted Fracture

- Similar to patellar fractures, this fracture involves the bone breaking into multiple pieces.

- Intra-Articular Fractures

- Occasionally, fractures can extend to your knee joint and actually cause the surface of the bone to separate into several pieces. This is the hardest type of fracture to treat.

Femur fractures can be open or closed. Open fractures involve fragments of bone sticking out of the skin, whereas closed fractures don’t break the skin. There’s typically damage to other tissue surrounding an open fracture. Because of this, they take longer to heal and also run a higher risk for complications.

When you break your femur bone, both your quadriceps and hamstring muscles tend to contract and shorten as a result. If this happens, it can be difficult for the bone fragments to line back up and heal properly because their positioning shifted.

Most distal femur fractures occur in younger people with high energy injuries, like a high-speed car crash, or in older adults with weaker bones. Unfortunately, the elderly are at a greater risk because of their poor bone quality due to age. Something as simple as falling out of bed or from a standing position can cause a distal femur fracture, especially if their bones are quite weak.

Some notable symptoms of distal femur fractures include pain when weight bearing, swelling, and (as odd as it may sound) your leg appearing shorter or crooked. Most of these symptoms are usually concentrated to the knee area, but may travel to the thigh area as well.

Diagnosing

Your doctor will examine your overall condition and see if you have any other injuries. They’ll also check to make sure the blood and nerve supply to your leg is ok as well.

Imaging, like x-rays, can easily identify a break. They can also tell what type of fracture it is and where it’s located. Your doctor may also order a CT scan to check the severity of your fracture.

Treatment

Treating a distal femur fracture depends on the severity of the fracture. The best thing you can do is get up and moving as soon as possible. Even it’s just moving from your bed over to a chair, or walking around the house. Treatment that involves movement early on, like physical therapy, is huge in reducing knee stiffness. It even prevents more severe problems caused by extended bouts of bed rest.

Proximal Tibia (Shin Bone) Fractures

If you break the part of your shin bone just below the knee, then you have something called a proximal tibia fracture. The proximal tibia is the upper area of your shin bone where it widens and forms your knee joint.

Similar to distal femur fractures, proximal tibia fractures can be transverse, comminuted or intra-articular depending on the break. The top of the tibia is made of a type of honeycomb shaped bone that is softer than the rest of the tibia. If a strong force pushes the tibia upward, the honeycomb part can compress and stay sunken in, like a piece of styrofoam. This can throw off your alignment and even contribute to arthritis and a loss of motion.

Most upper tibia fractures are caused by trauma, but can also be a result of stress. Younger adults typically see these fractures during high energy injuries, such as a sports injury, car accident, a long distance fall. Due to their poor bone quality, most older people see these fractures from a lower energy injury, like falling from a standing position.

Common symptoms of proximal tibia fractures include pain while weight-bearing, swelling, limited range of motion, foot numbness, and even a deformity where the knee may look slightly “off”.

Diagnosing

One of the first things your doctor will do is examine your injured knee and the surrounding area. Depending on your symptoms, they will want to make sure your blood supply and nerves aren’t having any issues that may be causing numbness or excessive swelling.

The best way to evaluate a potential fracture is with imaging. Your doctor can use x-rays to get a clear image of the bone to see the type of fracture, as well as the location of the break.

If you do have damage to any surrounding soft tissue, your doctor may order an MRI. They might also order one if you’re showing all the signs of a proximal tibia fracture but the x-rays come back negative. In this case, the MRI might be able to detect a reaction in the bone marrow which indicates a fracture has occurred.

Treatment

Treating a proximal tibia fracture can be done with or without surgery. Most active individuals choose the surgical route so they can maximize their joint motion and stability, as well as minimize their risk for developing arthritis. Older, less active adults usually opt against surgery since the benefits are limited and the risks are higher.

Nonsurgical treatment typically includes some sort of bracing or cast to keep your bones in line and healing properly. You’ll also have restrictions on weight bearing activities and certain movements in the beginning, but they will change as you heal.

While it’s important not to overdo it when you have a shin bone fracture, it’s equally important to begin safe, gentle movement to prevent stiffness. At physical therapy, your doctor will create an individualized program to do just that. They will recommend different modifications and work with you to help you regain your function and strength.

Click here to learn more about how Borja Physical Therapy can help treat your knee injury.